I want to be candid: my ethics are imperfect.

I spent four years designing an NYU degree on the ethics of visual journalism in the digital age, and the past two putting theory into practice—as a writer, editor, and freelance photojournalist. I’ve dedicated my entire early career to photojournalistic ethics, and still, my ethics are not perfect. They’re far from it.

The more I study and practice photojournalism ethics, the more I realize: there is no such thing as a perfect ethic. I thought I could eventually define a code—my senior thesis—that would last us our whole careers. And I did, briefly. I was right, and then I was very wrong.

This is why I want to be completely transparent. We are all on a journey toward ethics—it’s our highest obligation as visual journalists, and it’s a necessarily ceaseless one.

Ethics must evolve. We have been evolving—photography has been undergoing a slow paradigm shift since birth, moving away from objectivism and into postmodernism. If we hadn’t changed, we might still believe cameras, as scientific mechanisms, to be capable of producing unbiased, fixed, and unequivocal truths.

But contemporary philosophies better understand human error, and the digital age presents new challenges to navigate—facial recognition, virality incentives, surveillance culture, deepfakes, digital permanence, and the sheer ubiquity of cameras. Today’s digital and political landscape demands that our ethics continue to adapt, and flow forward.1

So why not be transparent—in our inquiry, in our mistakes, in our shortcomings, and the damage we’ve done or are capable of doing? Photos are intrinsically political. They hold weight. They freeze time, elicit emotion, spark action, and change laws. We must be radically honest and radically communicative, because honesty and communication breed truthfulness and earnestness. This is the photojournalism I believe in; this is the world I believe in.

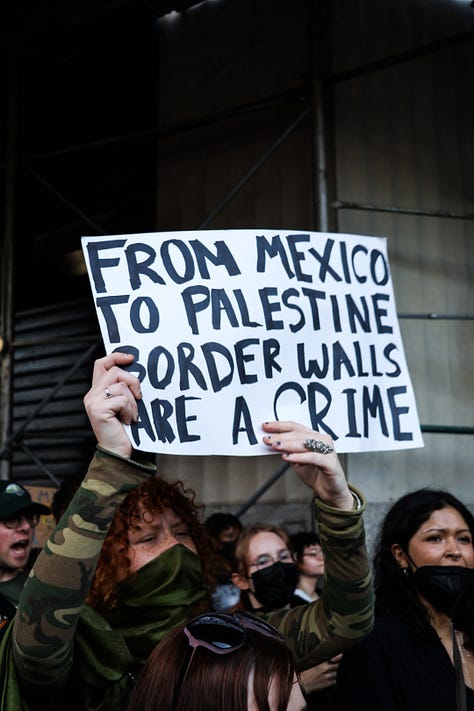

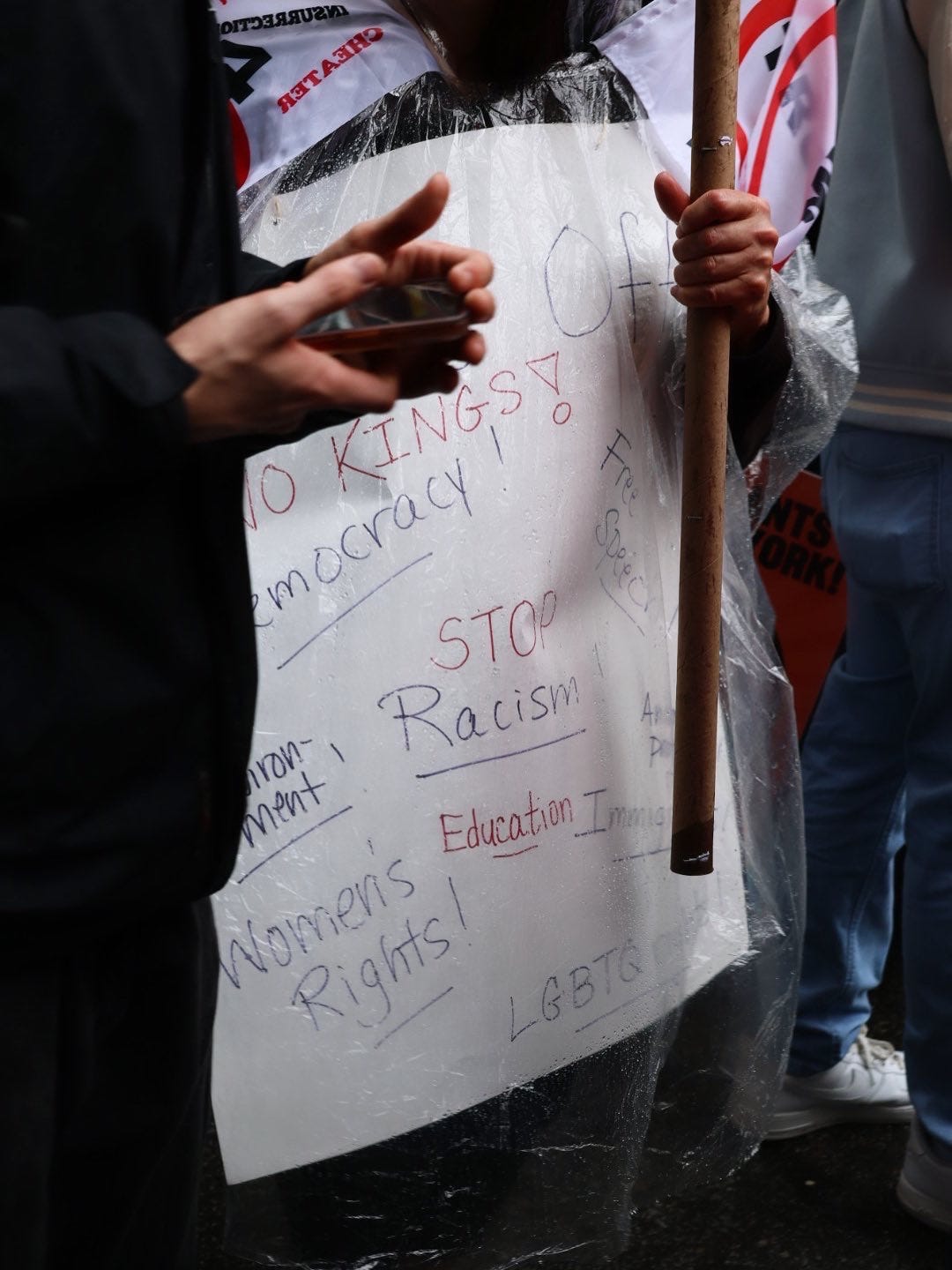

I covered the anti-ICE and No Kings protests this week. Every photographer seems to have a different ethical approach to protests. Protests are complex spaces, involving layered questions of identity, engagement, safety, and more:

When should we hide faces? And whose? When is obscuring identity a form of protection, and when is it erasure? And whose responsibility is it—the subject’s, the photographer’s, or the editor's? When should we ask for permission in a public space? What exactly does nonverbal consent look and feel like? Should we photograph children—and under what conditions? What’s the difference between engaging and interfering? Should we be nonpartisan—are we ever? Can we chant, march, cheer, wear signs, or help? If not, why?

I have my answers. Many have changed over time. I’ve learned ethics can’t be learned through theory or practice alone. Some rules that made sense in study fell apart in practice, and the frenzy of practice can cause you to forget what you need to remember.

The following are reflections on moments I had at the protests, involving identity, photographing children, ego, safety, and engagement. I don’t share them to be didactic—I’ve never believed in one-size-fits-all. I share them to spark critical thinking. In an occupation like ours, asking the right questions is better than having the right answers. I have answers for me, but I don’t have answers for you—just experiences and reflections to share, and the hope that they invite your questions too.

EGO

Picture this: 6’1. Aspiring conflict photographer. Hero complex. Leica. Unresolved trauma. Mommy issues. Still living in photojournalism’s golden age, quietly praying for another Vietnam War to photograph. That guy.

I know this archetype well. I was surrounded by him at NYU. I call him the Tisch bro.

Too many of us are Tisch bros on the inside. We’ve all chased praise, whether we admit it or not. That respect we felt for the honorable ones who came before us—we’d be kidding ourselves if we said we didn’t want to be admired the same way. It’s part of why we chose such a difficult career.

But there comes a point in every emerging photographer’s life when they have to hold a mirror to their ego. It’s hard to admit your reasons might be ego-driven, and just as devastating to realize that the form, at its best, elevates and informs, and at its worst, exploits and commodifies. There’s an uncanny feeling: awareness of intrinsic power dynamics and true devastation makes you hate your camera more with every shutter.

I’ll never forget how Natalie Keyssar described receiving her first major award. It was a red carpet event—Hailey Bieber was there, she told me. She was getting real industry recognition, and people kept telling her how brave she was. They’re the brave ones, she responded. She was being celebrated for her photographs of the political and humanitarian crisis in Venezuela.

I hated it, and I hated myself for it. When you get what you want, it’s never what you thought it would be—it’s much more complicated than that.

That disillusionment, that self-loathing, seems to match any starry-eyed, ego-driven idealism that came before it, and the pendulum continues to swing until we reach a kind of equilibrium. An honest acceptance of the true meaning of the work.

This, I believe, is the ego death of the photojournalist.

You have to confront the ego that brought you here. In other words, you have to kill your inner Tisch bro.

PROTECTING IDENTITY

Pixelating. Not everyone does it—in fact, it’s rare for photographers to do. I think that working as an editor has given me a heightened understanding of the idea that even though we have editors as the last line of ethical gatekeepers, they can make mistakes too. I make an effort to nip risk in the bud and be aware of any potential harm that can be done by any photograph I keep or share.

Although protestors often chose to obscure their own identities with masks or otherwise, many do not—either because they intend to be seen, or because they didn’t think twice about it. As photographers, whose job is to visually organize chaos, we often don’t have the time or ability to discern our subjects’ intentions.

But based on a sign held by this individual at an anti-ICE protest, which implies that the subject may or may not be of documented status, I decided to pixelate his portrait. Doing so certainly weakened the strength and emotional impact of the frame, but protecting identity takes precedence. As one of my mentors, Katie Orlinsky, used to say, it’s people over photos, every time.

PHOTOGRAPHING CHILDREN

I’m in a constant state of learning, unlearning, and relearning on this topic. There is one thing I do know: children have a unique and sacred ability to move us, and should be seen in the world and as part of history.

That being said, it’s important to understand context in public and private settings, and to respect independent agency as well as their guardians’ role in a given situation.

For me, photographing children is a case-by-case ethic, guided largely by real-time intuition. I’ve chosen not to release the shutter at some ineffable feeling in my gut. I’ve chosen to delete images after the fact for the same reason.

Editors must be especially purposeful when running images of children in distress. For example, publishing photos of starving or injured children in Gaza can shed critical light on those realities, and these images, because of the emotional weight children carry in the public eye, have an incredible capacity to spark curiosity, empathy, and social change. At the same time, they run a critical risk of retraumatizing subjects or effectively desensitizing the public. Enormous care is required when photographing kids.

SAFETY

As protest photographers, we are obligated to a baseline of medical and safety training. I am hostile-environment certified by Head Set Immersive. Their XR course also covers stress management and emergency response basics for hostile environments. I’d highly recommend it if you plan to work or continue to work in these spaces.

ENGAGEMENT / INTERFERENCE

I don’t pretend to be an objective observer. I am a witness, and my highest responsibility is to relay information in pursuit of truth. Becoming overly engaged can obstruct that pursuit, but there is no reason to refrain from lending a hand, returning a smile, or asking to take someone’s photo.

That being said, I don’t stage, direct, move, or interfere with people or objects. When this is done, photographs leave the documentary space and bridge into art.. or something else entirely. Recently circulated videos of press photographers staging their frames at the LA protests make clear why that boundary matters.

I’m not a machine—I photograph what I see, what I find worth seeing. For example, if I hadn’t known who I will be ranking in the NYC mayoral election, I wouldn’t have been as compelled to photograph an anti-Cuomo sticker.

People can and will draw their own conclusions from what they see. But because they’re seeing what we photographers have chosen to see, what the subjects have shown, and what the editors have selected, we inevitably become part of the story—and we carry a degree of diplomatic responsibility.

I am human. And so long as I can pursue truth standing on its own two feet, I will engage.

These are my ethics as they move in today, and will continue to move into tomorrow, becoming more and ever more like a river than a rock.

In Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche describes truth as a woman. Ethics and truth have the same spirit—they are both fluid, dynamic, and elusive. And we should let them be. Supposing truth is a woman—what then? Is the suspicion not well-founded that all philosophers, insofar as they have been dogmatists, have failed to understand women—that the terrible seriousness and clumsy obtrusiveness with which they have usually approached truth have been unskilled and unseemly methods for winning a woman?

This! All of this! So much. I’ve battled with my own internal conflicts and then witnessing the actions of others. It’s refreshing to read we are still trying to work while always making people’s safety a priority and not winning an award as a Tisch bro. (I usually compare them to “ambulance chasers” and they’re the ones that can’t even tell us their persons name - let alone protect their livelihood. Or risk everyone’s safety by rushing to the aftermath of a traumatic event without any medical training.)

I’ve always said I’m human first, a photographer second and it’s beyond inspiring to see we are a growing majority. I’d love to chat and rant about all this someday. Keep up the great work but also keep saying and sharing what needs to be said! 👏🏿